The UnderWater Unit (UWU)

SUTD and SOAR’s UnderWater Unit is the single most exciting project I’ve ever worked on. As I write this, we are preparing for SAUVC 2025 - an annual contest the team participates in. The contest is our annual progress-checker: a deadline by which we ought to be making significant progress by.

The task after SAUVC 2024 was defining ‘significant progress’.

SAUVC 2024

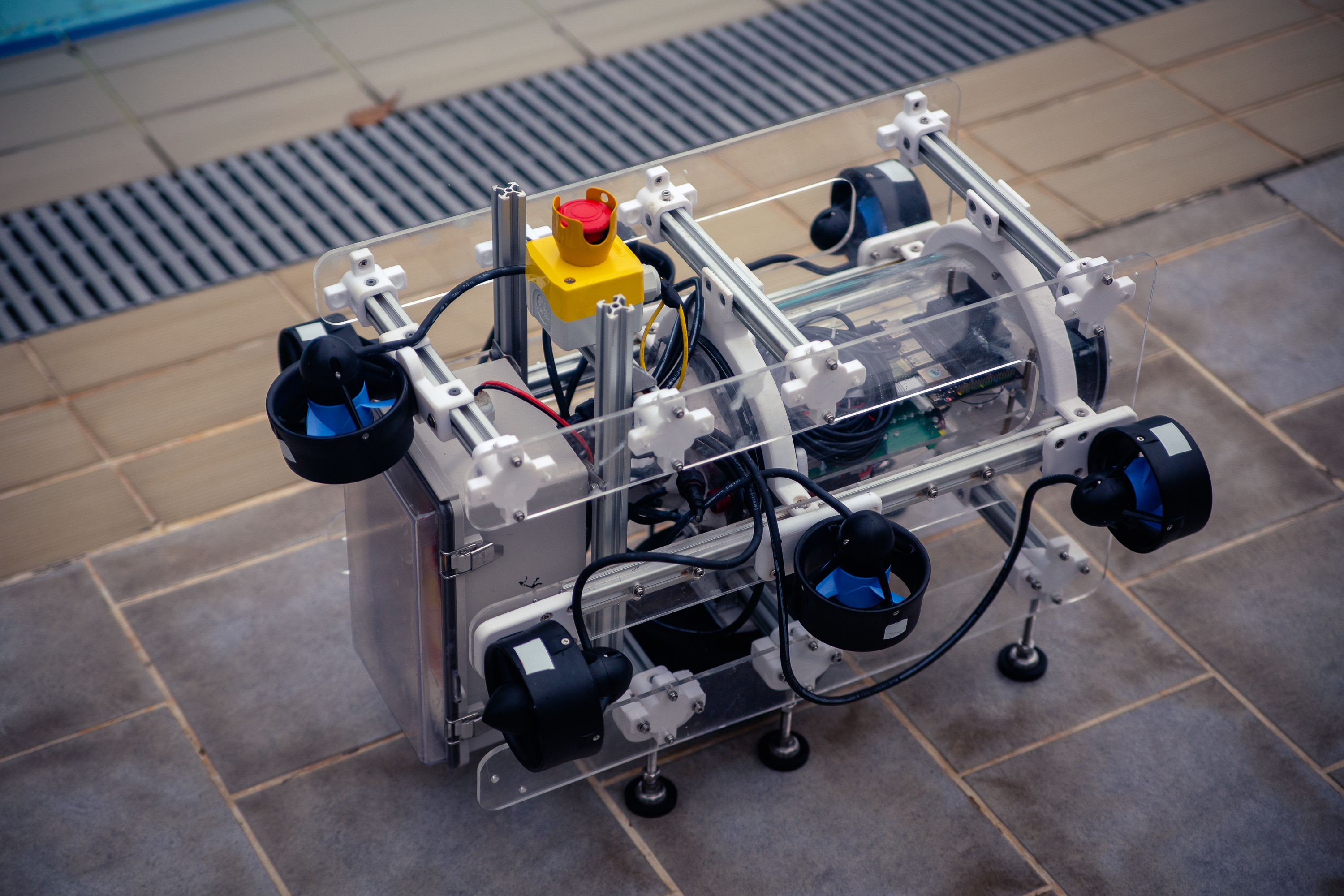

SAUVC 2024 happened in April 2024, following an extremely tight development period where the team completed and waterproofed a fully working underwater navigation unit named ‘Blobfish’. I, along with several members of the current team, joined the project at the 11th hour and began writing navigation algorithms for it. The idea was to use traditional CV methods and OpenCV to detect obstacles and send messages using the ROS2 platform setup by my seniors to an Arduino node, which then instructed a series of motors to avoid the obstacle. However, we very quickly ran into problems. Traditional CV methods meant that we had to hardcode what the software would key out, meaning there was a fixed range of blue hues that the program would ignore. This was done in order to ignore the background of a swimming pool which generally fell into this range of hues. This program did not account for the fact that water absorbs wavelengths of light that the obstacles reflect, turning them into another darker/lighter hue of blue, which the program would then ignore. Along with this, on contest day we found that the pool was bordered by a checkerboard pattern that only made things worse for our poor bot. Despite the odds, the bot successfully avoided an orange obstacle, but was not able to turn fast enough to avoid it completely, thereby disqualifying us on the final day.

This among many issues that we’d discover later became what we defined as ‘significant progress’.

- The bot needs to know where it is.

- The bot needs to identify what’s around it.

- The bot needs to respond faster to what’s around it.

My team (myself, John-Henry Lim, Ng Tricia, Aryan Gupta) inherited this project from our seniors who journeyed away with the elves after contest day (they began their final year in engineering).

Development Hell

After a four month break, we were back to work and my team was now fully in charge of developing, publicizing and recruiting for UWU. We had our responsibilities to the project and to the student organization we were a part of. My vision of UWU was something along the lines of a development hub - a haven for people of many levels of robotics knowledge - a place free of the cutthroat nature of competitive robotics - a community that newbies weren’t intimidated by. I started by creating this poster in October 2024, leaning into the absurdity of calling the project UWU.

The idea worked! Within two weeks, we had about 50 freshmen joining our hub, and interest in the project seemed strong. However, interest alone can carry people only so far. By the end of the term, we had to start taking interviews and form a core team of 11 (including the five original members) that we would work closely with, which already locks the majority of development away from the community. As much as a community project idea is cool, for efficiency purposes, I ended up learning why exactly it’s hard to maintain.

At the same time, our team was still in the process of figuring out how to work with each other. Up till then, the five of us were under the steady guidance of our much more experienced seniors. Now, we were like fish out of water guiding the school onto land. We hadn’t found our ‘groove’, and noone really knew how to work with each other. One thing we knew for certain was that we needed to qualify again for SAUVC 2025, which required that we have the bot move in a straight line underwater for 15 seconds. Seems simple right?

Here’s a list of the issues we discovered on top of the progress we needed to make by March 2025.

- The endcaps had loosened, letting small amounts of water in.

- The Jetson Xavier we were using had a major boot-up issue.

- The PID (Proportional, Integral, Derivative) algorithm we were using to keep the bot steady underwater, and perform basic movements, was incomplete and not generic enough to account for all positions the bot could be in.

- The USB tether that provided us a wired connection to the Jetson had worn out.

- Occassionally, the Arudino bridge node would say that there’s no Arduino detected even though the connection was secured on a hardware level.

None of these issues were the fault of our seniors; considering their extremely small development time, what they achieved is nothing short of a miracle. However, by November, we had to submit a video proving that the bot could move in a straight line. Our team, now paralyzed by pressure of a rapidly approaching deadline, had to take a moment to breathe. This point in the project proved to be critical, because I had the opportunity to understand how large scale projects are maintained and developed despite disagreements and disputes within the team.

In a maddening 6 weeks, we managed to fix these issues, terrify the juniors who joined the project and added a framework that makes the bot listen to a list of commands we write out in a YAML file. I ended up learning the basics of ROS and asynchronous programming.

Here’s a demonstration of the PID algorithm telling the motors to rotate so that the bot compensate for what direction it’s being turned. Effectively, we’re trying to make it stay in one place by applying an equal and opposite torque.

Finally, after a lot of coordination with the weather, negotiation with hostel staff and rounds of frustrating attempts, we pulled together and filmed our successful attempt.

The damn thing changed lanes while turning too.

I’ll be updating this blog with progress from the next few months as it happens.

To be continued!

The continued:

After recruiting 5 new team members, UWU continued onto 2025. We had 3 months to go, a fresh OAK-D camera to play with and I really wish I hadn’t started this sentence like it was a list.

Summer in Singapore is truly lovely, a problem we ran into almost immidiately during extended pool tests was that the camera would eventually turn itself off to prevent heat damage. The harsh sunlight combined with our bot’s outer surface being a sealed tube of acrylic (effectively turning it into a greenhouse) was quite literally cooking the project alive.

Camera stuff

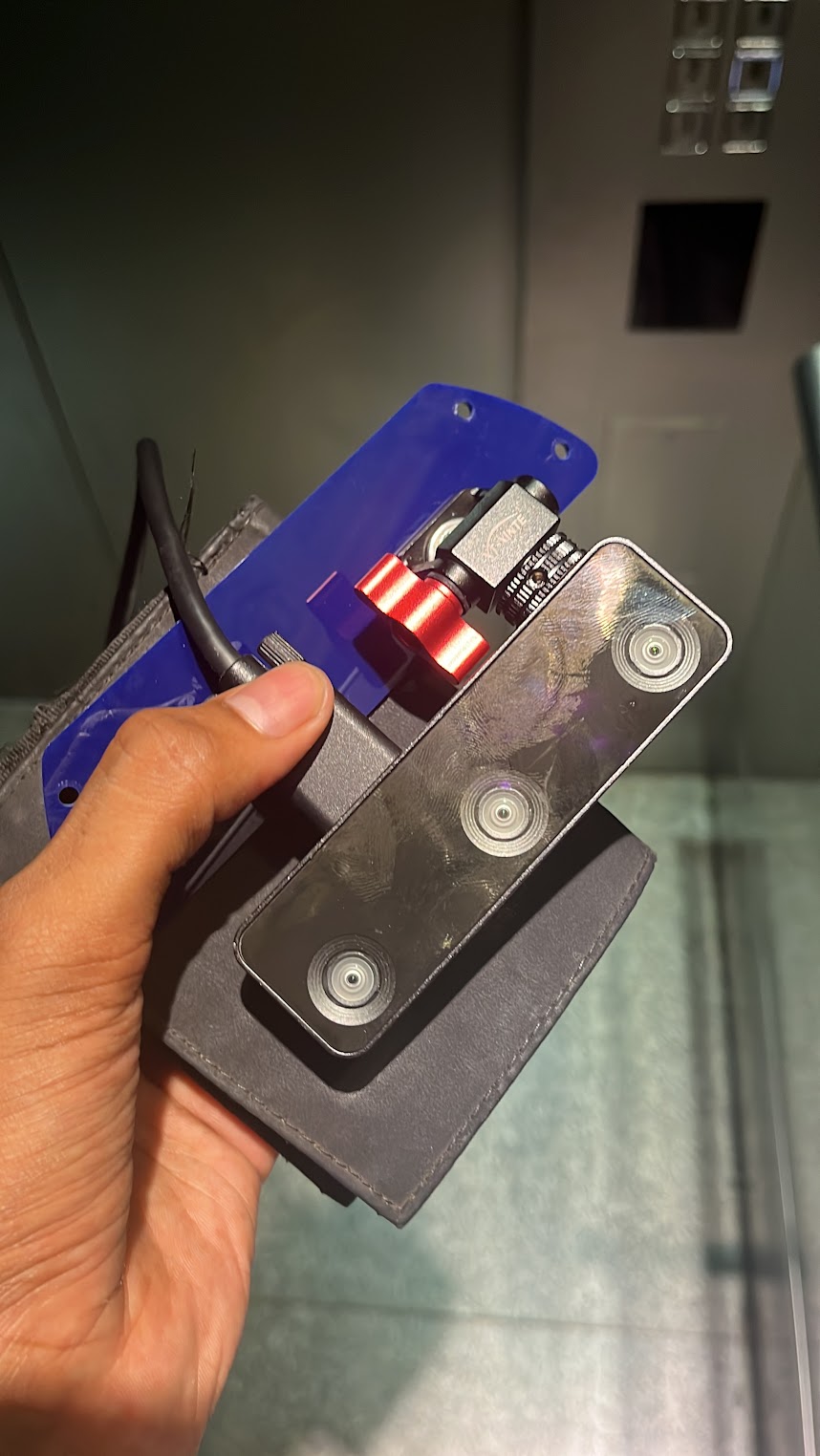

The OAK-D is a ridiculously powerful camera and it was meant to play a huge part in the robot’s localisation (essentially, getting the robot to know where it is relative to its surroundings). The robot also has a VectorNAV IMU, which we’d use for our odometry. Now this IMU comes with an interesting quirk where if we turned it upside down, it measured gravity differently than it would’ve right-side-up. Why? Who knows. To account for this, we also had a depth sensor attached to the bot. If you were to divide the pool into an XYZ coordinate system, the IMU is responsible for telling us the XY.

However, all IMUs come with a drift component which causes its estimated position to change over time. This happens because the IMU is calculating its current position by just integrating the accelration values it recives in the X, Y and Z axes which each carry a small amount of measurement error. The measurement error, during integration, increases quite a bit, which results in the calculated position to vary. To account for this, we had to fuse the information we get from the IMU to the estimated position from the camera which used visual odometry methods.

I took almost every opportunity to unplug the camera from the robot and play with it in my room.

Together, they fuse using the EKF (Extended Kalman Filter) and we have a relatively stable approximation of where the bot is.

Now, all of that did very much come together only days before the contest. In fact, we had working odometry only halfway through the 3-day contest.

In addition to this. because of how water warps light differently to air, we also needed to recalibrate our camera. Why? It’s because the visual odometry information coming from the camera is calculated partially based on the disparity between each frame. The OAK-D camera is a stereo camera, so the way it knows how far away an object is, is by first matching a number of features between the frames recieved by both cameras, and then finding the differences in their positions. Objects that are further away from the camera would naturally have less difference in their positions according to the left and right camera the same way a faraway object would appear relatively in the same place to our left and right eyes. However, due to water having a different refratctive index compared to that of air, we would not be able to, with the same degree of accuracy, gauge how far away something is underwater. Which means that it would be even more complicated to make a machine do it.

Now, even in air, camera lenses distort light to some degree, which is why images can appear warped. The best way to account for this is through camera calibration, which involves capturing several images of a checkered charuco board. The vertical and horizontal lines on the checkerboard (which would oridinarily be straight) provide a good reference for how much the image warps, so that when the image is processed it can be rectified. Doing this on land is relatively straightforward, but the process also does need to happen underwater because of how light refracts and distorts differently underwater. Without a rectified image, points on the edges of the frame (with the maximum amount of distortion) would have inaccurate information pertaining to how far away those points are to the camera. Unfortunately, due to a lack of time this wasn’t an issue we could really get around, but trying to get the camera calibrated underwater was a fascinating experience. 11/10, would not do again.

Finally building on all this was our navigation stack. With a reasonably ok estimation of distances, we were able to strategically divide the pool into 1m X 1m squares. Our goal was to avoid a big orange flare (the position of which would be known to us) and pass through a rectangular gate made of pipes.

Here’s a demo: